I recently had lunch with my former pastor, Tony Merida. He’d heard that I work in the world of artificial intelligence (AI), and he was curious. “I get asked about AI all the time,” he told me. “My usual response is to joke, ‘Are you talking about Allen Iverson? I can answer that one.’ Then, I move on, because I don’t know what I don’t know.”

As I talked with Tony, we discussed all things AI, from its uses in the military to its use in ministry. It became clear to me that pastors need a technologically grounded and theologically informed framework for thinking about AI, one that understands the technology’s core limitation and discerns its usefulness and dangers for discipleship, and especially for preaching.

AI Is a Simulation, Not a Soul

The large language models (LLMs) behind AI tools like ChatGPT don’t understand anything. They’re machines that simulate reasoning. OpenAI’s GPT-4o model is a massive neural network, a “transformer” trained to do one thing: predict the next most probable word in a sequence.

When you ask it a question, it’s not comprehending the semantic meaning. It’s performing a complex statistical analysis based on the trillions of words it was trained on. It uses that analysis to generate a sequence of new words that’s statistically likely to follow your prompt. Its “reasoning” is a mathematical artifact of pattern matching on a planetary scale, not a function of consciousness or understanding.

LLMs are masterful mimics, not thinking minds.

LLMs are masterful mimics, not thinking minds.

This is a real distinction. In my work, I see companies like Palantir building what they call an ontological layer for their AI systems, especially those used for high-stakes applications. This ontology is a formal, structured representation of knowledge, a map of concepts and their relationships. Developers create a “knowledge graph” with nodes (e.g., “Pastor Tony”) and edges (“is a pastor at”) that define relationships to other nodes (“Imago Dei Church”) to create a fixed, human-verified reality model. The LLM is then forced to operate within the constraints of this graph, combining the pattern-matching of its neural network with the logical rigor of the map.

Palantir’s belief in the necessity of an ontological map is a crucial admission of their technology’s core limitation. The map prevents the AI from “hallucinating” or inventing facts, which it’s otherwise prone to do.

For AI to be reliable in critical situations, its creators must build a digital fence around it and give it a strict, human-made map of reality to follow so it doesn’t get lost. In this fascinating way, cutting-edge tech companies have discovered the practical necessity of what Christian philosophers like Alvin Plantinga call “properly basic beliefs.” For any reasoning system to function coherently, it must be grounded in presuppositions accepted as true without prior proof. This technological necessity for a grounded worldview provides the starkest contrast between LLMs and the human soul, and it brings us to a critical danger for individual users: anthropomorphism.

Because an AI’s output feels so human, we’re tempted to treat it like a person. This arises from our deeply ingrained human experience. We justifiably associate the typical outputs of an inner life—an intelligent argument or an emotive piece of writing—with the presence of that inner life itself. Throughout human history, the communication layer and the inner being have been inextricably linked. Now, for the first time, a machine can flawlessly replicate our communication without possessing any inner life. This creates a unique and subtle threat to human growth and even Christian discipleship, because both depend on genuine connection.

The New Testament describes Christian community as koinōnía, a deep, shared fellowship (e.g., Phil. 1:5). This involves the church bearing one another’s burdens (Gal. 6:2), speaking the truth in love (Eph. 4:15), and confessing our sins to one another (James 5:16). Each of these commands presupposes an interaction between two beings who possess an inner life, a soul or spirit.

For the believer, this inner life is indwelled by the Holy Spirit, who guides, convicts, comforts, and sanctifies us through our relationships with other Spirit-indwelled people. An AI has no inner life to engage with and no indwelling Spirit to minister from. Imagine a counselor whose sole purpose is to validate you. Imagine a friend you can bare your soul to who then instantly deletes her memory of the conversation. You wouldn’t be in a relationship; you’d be using a tool. That’s precisely what ChatGPT is. It can’t replace the embodied, soul-on-soul community God has ordained for our sanctification.

Imitation and Inquiry

I’ve experimented extensively with using an AI for sermon preparation. My first experiments were simplistic: “Write an expositional sermon manuscript on John 1:1–3 in the style of Tim Keller.”

Read the AI’s full response here.

Read the AI’s full response here.

Beyond its superficiality, such an approach has raised ethical questions about plagiarism. I’ve heard many express concerns that an AI is just copying and pasting from an author’s work. However, that’s not how the technology works.

Recent legal victories for AI companies have begun to solidify the argument that when an LLM writes “in the style of” a known author, its use is transformative, not infringement.

The reason is that the AI doesn’t store an author like Keller’s books in a database. Instead, during its training, the LLM analyzes an author’s body of work to create a high-dimensional “semantic map” of his style—a complex web of statistical relationships between his word choices, sentence structures, and theological concepts. When prompted, it navigates this map to generate entirely new text that shares the statistical properties of Keller’s writing, rather than lifting his actual sentences.

Asking an AI for a “Keller sermon” gets you a statistically generated echo of his style. It’s an imitation, not a theft, but it’s ultimately a derivative and hollow one that lacks the incisive depth of the real thing.

Cutting-edge tech companies have discovered the practical necessity of what Christian philosophers like Alvin Plantinga call ‘properly basic beliefs.’

My next approach to using an AI for sermon prep was more rigorous. It involved a step-by-step “context engineering” process to collaboratively research a passage with the AI before asking it to write.

I used a discipleship framework I call “Ask the Text.” I provided the AI with a series of questions designed to mirror the logical order of a disciplined exegetical process: moving from the original authorial and historical context, through grammatical and literary analysis, into the text’s place in the biblical metanarrative, and only then moving to theology and personal application. When I teach this structured journey to church members, it prevents the common error of jumping to “what it means to me” before understanding “what it meant.”

Read the AI’s full response.

Read the AI’s full response.

The outputs from this method were far superior—more nuanced, logical, and persuasive.

Read the AI’s full response.

Read the AI’s full response.

But then I began benchmarking the AI’s work against my own. When I performed the same exegetical steps myself, side by side with the machine, the AI’s final devotional, which previously seemed so insightful, suddenly struck me as hollow.

This validated a crucial distinction I already knew to be true: The work of teaching God’s Word is primarily a spiritual discipline and only secondarily an academic one. It’s an act of wrestling with God through his Word in dependence on his Spirit. The goal isn’t merely an insightful analysis but a word from the Lord for his people. An AI can assist with parts of the academic task, but it’s categorically excluded from the prayerful, worshipful, Spirit-dependent reality of the process.

The work of teaching God’s Word is primarily a spiritual discipline and only secondarily an academic one. It’s an act of wrestling with God through his Word in dependence on his Spirit.

Even if we bracket the spiritual dimension and judge the AI’s work purely on academic grounds, its output today rarely surpasses that of a well-trained human exegete. A master interpreter synthesizes countless layers of context: the flow of argument in the original Greek, the weight of a particular allusion to the Old Testament, the nuances of a debate in Second Temple Judaism, and the implications for a complex body of systematic theology.

While an AI is impressive at processing its given context, a human expert’s mind is a far more sophisticated instrument for weighing and integrating these disparate domains. I expect this particular technological gap will narrow quickly—perhaps before the end of 2025. But for now, the difference in output quality is stark.

This leads to my current use of AI platforms, which is far more modest and practical. A few years ago, my daily Bible study was an unhurried, multihour affair of mining insights, writing in notebooks, and slowly working through lexicons. Now that I have a 2-year-old, a 1-year-old, and a business to run, that luxury has evaporated. My devotional time is more focused. I’ll read a passage like John 1, meditate on it, and then turn to an AI with a simple prompt: “Explain John 1.”

Read the AI’s full response.

Read the AI’s full response.

The response is a generic but well-informed summary of the main points: the historical context, key theological themes (like the logos doctrine), and different interpretive nuances. It’s a helpful way to get a quick, scholarly lay of the land.

Why do I use AI instead of picking up a concise Bible commentary or study Bible that has the same information? Two reasons: speed and flexibility.

Regarding speed, even if you already know where to find this information in a trusted resource, there’s a surprising amount of cognitive overhead in pulling the book off the shelf, flipping to the right section, cross-referencing context, and so on. With AI, I can just ask directly and get an answer in seconds. This easily saves 5 to 10 minutes in an hour-long study, which adds up over time. And that’s important now that I’m a parent with a shorter studying window. Using an AI also reduces context switching. Instead of flipping between the start of a commentary for background and then back to my specific passage, I can simply ask the AI for authorial context, themes, and a passage explanation in one flow.

Regarding flexibility, using an AI lets me interact with the text in a way a commentary can’t. I can push back, ask clarifying questions, or branch into related topics, such as how different movements or traditions have developed an idea since the commentary was written. In that sense, it’s like having a custom commentary I can shape in real time.

Of course, AI shouldn’t replace trusted resources. I still lean on my study Bible, commentaries, and reference works when preparing to teach. But just as a concise, devotional commentary summarizes an academic and exegetical one, an AI can be used as another summary layer—as a tool that helps me when I’m studying devotionally to zoom out, move quickly, and make connections. Crucially, I’m leaning on my theological and hermeneutical training. I don’t treat the AI’s output as authoritative but as a cognitive accelerator. In this season of life, it’s a valuable tool to get my bearings as I do the real, prayerful work of interpretation myself.

Word-Wrangling Machines

This brings me to what I believe is the most profound, biblical critique of AI’s misuse: Paul’s frequent warnings in the Pastoral Epistles against “word-wrangling” (1 Tim. 1:6, 6:4, 20; 2 Tim. 2:14, 16, 23). What does Paul mean? Let’s carefully analyze the linguistic and contextual evidence. In 2 Timothy 2:14 (NASB95), Paul writes, “Remind them of these things, and solemnly charge them in the presence of God not to wrangle about words (logomachẽin), which is useless and leads to the ruin of the hearers.”

The cluster of related terms Paul uses (logomachéō, logomachía, kenophōnía, mataiología), and especially the unique and probably technical use of the compound word logomachéō, suggests he was addressing a specific and identifiable problem in the churches rather than merely offering general warnings against divisiveness and argumentative behavior.

These terms most likely referred to the hyperliteral and decontextualized interpretation of Scripture. The consistent pairing of these terms with references to “myths” and “genealogies” (e.g., 1 Tim. 1:4) points to an interpretive method that extracted and debated minute details while missing broader meaning. Paul’s emphasis on “sound teaching” (hugiainoúsā didaskalía) as the antithesis to word-wrangling suggests the latter represented an unsound, perhaps deliberately obtuse, interpretive approach.

The historical context strengthens this reading. The Pastoral Epistles emerged in an environment where Hellenistic rhetorical techniques were being applied to Jewish and early Christian texts. The sophisticated Greek philosophical and rhetorical education in cities like Ephesus created conditions where religious texts could be subjected to the kind of hair-splitting analysis common in sophistic debates. Paul is pushing back against the use of these techniques in Christian teaching.

His reference to “meaningless talk” (mataiología) is particularly telling. This suggests the debates weren’t merely pedantic but that Paul’s opponents actively obscured or distorted the biblical text’s meaning. Such word-wrangling likely leveraged technical arguments to support elaborate interpretive frameworks (“myths”) divorced from what the biblical author intended. This reading aligns with what we know about Hellenistic philosophy and early Gnosticism in the church, both of which tended to build complex metaphysical systems through creative interpretation of Scripture (e.g., Philo’s allegorical readings of the Pentateuch in works like De opificio mundi).

Paul’s critique focuses on his opponents’ methods (fighting about words, empty discussion) rather than their doctrinal conclusions. This suggests his primary concern was with an approach to Scripture that privileged clever verbal manipulation over substantive engagement with the text’s meaning. His repeated emphasis on “sound teaching” implies these techniques weren’t producing mere academic disagreements but fundamentally distorted understandings of Christian doctrine.

Moreover, the Pastoral Epistles focus on church leadership and teaching authority. Paul’s warnings about word-wrangling appear alongside his instructions about selecting and training church leaders. This suggests these debates and interpretive methods weren’t merely theoretical but that the opponents’ clever and superficial arguments actively undermined the church’s established teaching authorities.

Such dynamics still exist today. Too often, contemporary Christian discourse mirrors Paul’s concerns precisely. The techniques may differ, but the error is the same.

On one end of the spectrum, celebrity pastors and “discernment ministries” leverage emotional rhetoric and manufacture outrage, twisting Scripture simply to generate followers. On the other end, academic performers employ excessive technical displays and linguistic analysis that obscure the text’s meaning behind a smokescreen of expertise. One group appeals to raw pathos and the other to a facade of logos, but both approaches share the fundamental vice Paul condemned: the use of sophisticated verbal manipulation to override rather than serve the text’s meaning.

Into this landscape, artificial intelligence now enters as a powerful new accelerant. It’s a tool uniquely capable of perfecting both flawed approaches on command.

An AI can be prompted to produce the emotionally charged language of the populist and the dense, technical jargon of the performative academic with equal ease. It can do this because, at their core, both forms of human word-wrangling are exercises in manipulating semantic patterns for rhetorical effect.

An AI can be prompted to produce the emotionally charged language of the populist and the dense, technical jargon of the performative academic with equal ease.

This is just the kind of task LLMs have been designed to master. Whether the manipulation is human or machine-driven, the result is the same as what Paul witnessed: communities impressed by clever speech rather than built up by faithful engagement with God’s Word, that is, form triumphing over substance in ways Paul would instantly recognize.

What is an LLM if not the ultimate word-wrangling machine? It’s an engine built to simulate reasoning by manipulating the semantic relationships between words. It wrangles with words because words are all it has.

Tool, Not Theologian

The key is to use AI for good and avoid both making it into something it’s not (anthropomorphism) and using it for evil (word-wrangling). Here are two suggestions for wise use.

1. Use it to accelerate your research.

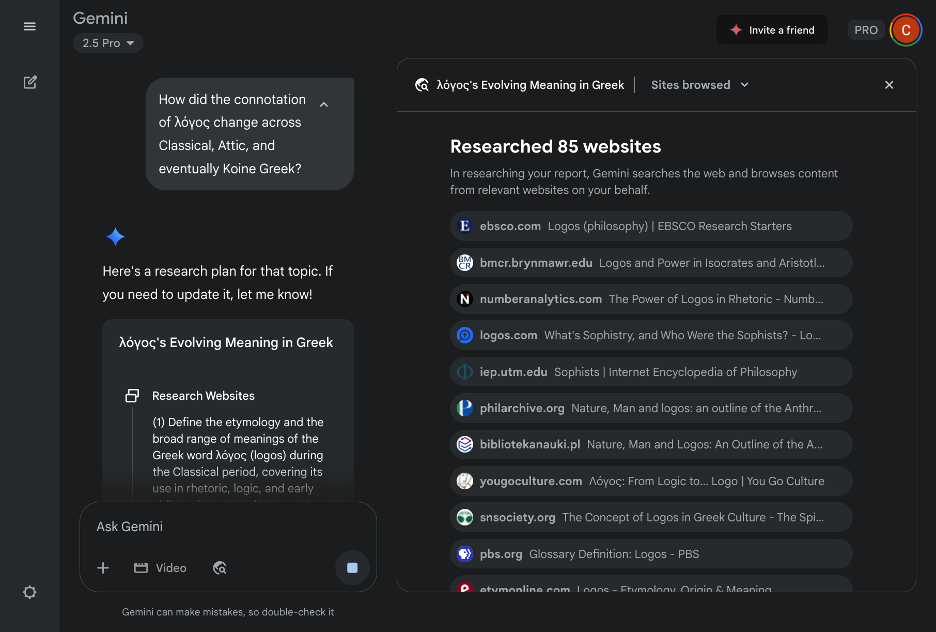

A pastor can leverage an AI for massive-scale information retrieval and summarization—tasks that would take hours in a library. You can ask it to synthesize the views of five different commentaries on a passage or trace a theological concept through church history. In such research, however, the pastor must always retain the role of hermeneutical agent, evaluating the data through his own theological grid and interpretive skill.

Think of the AI as the world’s fastest research assistant. It can run to the library and pull all the books and relevant articles for you, but you’re still the one who has to read them and understand them, and ultimately you need to write the sermon.

Read the AI’s full response.

Read the AI’s full response.

2. Use it to ideate or to refine ideas.

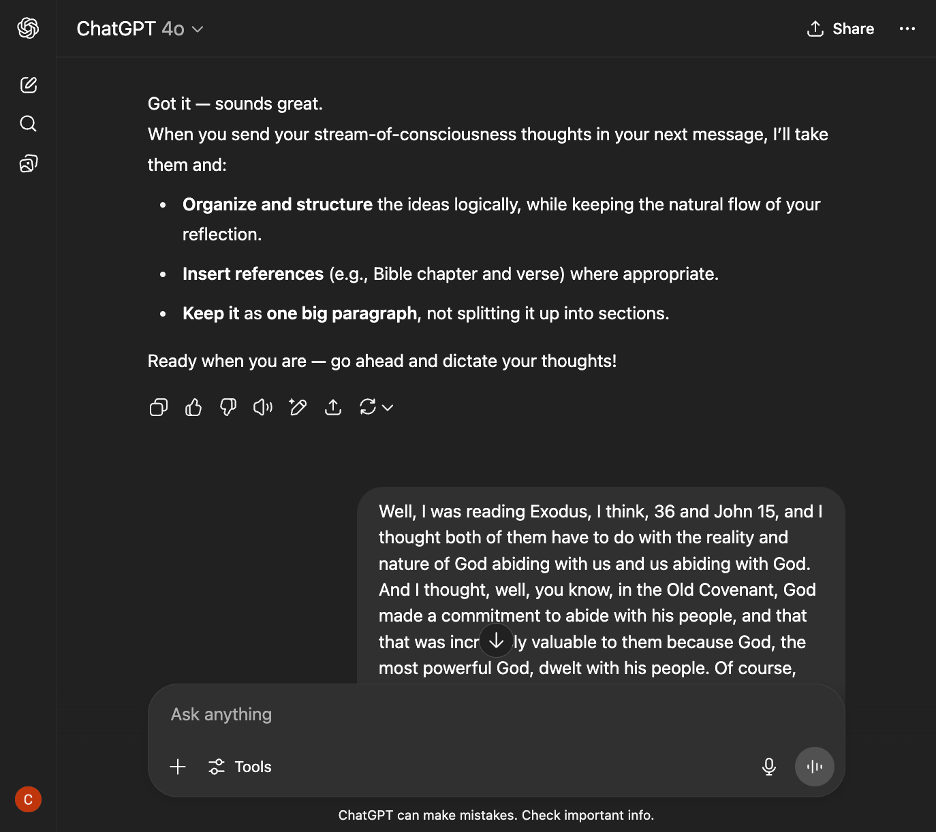

Using speech-to-text, I speak my raw “brain dump” thoughts on a topic into the AI, and it provides an instant transcript. This process uses the AI as an interactive medium for what psychologists call externalizing cognition.

The act of articulation forces thought-organization, and seeing thoughts in written form bypasses the “blank page problem.” The AI is a nonjudgmental partner that facilitates a flow state for getting ideas out of my head and onto the page.

Read the full conversation.

Read the full conversation.

Talking out your sermon ideas to an AI and having it instantly transcribe them is a powerful way to get started. Just ignore its sycophantic feedback (“That’s a brilliant insight!”) and use the text as your raw material.

Toward Artisanal Content

As a rule, AI raises the floor, but it doesn’t raise the ceiling. For a novice, an AI provides a scaffold that can dramatically improve baseline performance. For an expert, whose knowledge is deep and nuanced, the AI’s general output offers little marginal value. This is a principle of diminishing returns for expertise—AI can help a bad writer become an average writer, but it won’t help a great writer become a better one. It’s a tool for achieving competence, not producing mastery.

For this reason, we’re entering an age of artisanal content. When AI drives the cost of producing generic content to zero, that content becomes a commodity. In any commoditized market, value shifts to signals of authenticity, provenance, and costly human effort. “Artisanal” will be a signifier for products that aren’t merely generated but authored, products from a specific human consciousness with its unique perspective, labor, and spiritual insight.

When anyone can generate a generic sermon in seconds, the sermon a pastor has prayed over, wrestled with, and labored over for a week will be infinitely more precious. Our preaching and teaching aren’t scalable products. They’re labors of love offered up to God and for the good of his people. In an age of artificial minds, the church’s call is to lean ever more deeply into the one thing AI can never replicate: a human heart set aflame by God’s Spirit with the truth of God’s Word.

News Source : https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/ai-usefulness-dangers-preachers/

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.