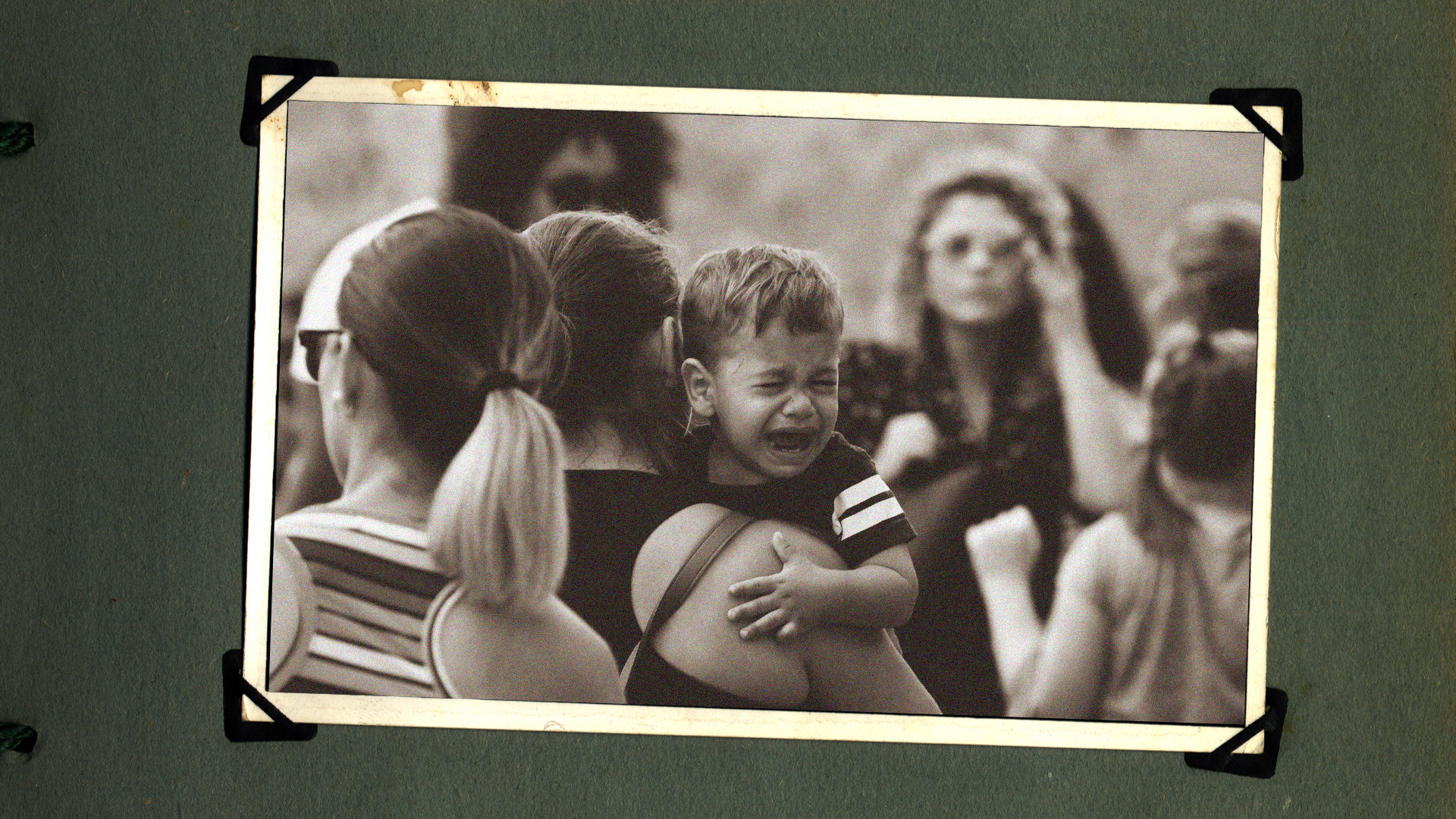

Before cellphone photo apps, many families kept bulky albums. Good memories—family trips, birthdays, and reunions—populated the pages. You didn’t usually find pictures that conjured unpleasant memories. Bad memories aren’t displayed; they’re discarded so people don’t have to relive them.

The Psalter is different. Psalms 105–106 contain both good and bad memories from Israel’s history—and rather than being kept private, these psalms were publicly sung in corporate worship (e.g., 1 Chron. 16). One of these unsavory memories is the period of the judges. During this dark time, the Lord repeatedly rescues Israel from idolatry (Judg. 2:11–13) and some of its symptoms, like mistreating women and children (11:29–40; 19:1–30; 21:20–23), national disunity (12:1–6; 20:1–48), and bondage to enemies (6:1–13).

At least three times in the Psalter (Pss. 68; 83; 106), writers allude to words and stories from the dark book of Judges. We should ask why, so we can grasp how unsavory memories helped the psalmists savor God’s grace.

Stabilizing Tentative Faithfulness (Psalm 68)

Psalm 68’s allusions to Judges are difficult to see until you compare verses 7–8 with Judges 5:4–5. David writes of “when [God] went out” and “when [God] marched” (Ps. 68:7; see Judg. 5:4); he recalls how “the earth quaked” and “the heavens poured” (Ps. 68:8; see Judg. 5:4) before “the One of Sinai” (Ps. 68:8, author’s translation; see Judg. 5:5).

Clearly, David is borrowing lyrics from Deborah and Barak. Despite a few differences (like saying “God” when Deborah said “LORD”), he uses 12 of the same Hebrew words in the same order. And the borrowing continues throughout the psalm—for example, in phrases like “among the sheepfolds” (Ps. 68:13; Judg. 5:16) and “leading . . . captives” (Ps. 68:18; see Judg. 5:12). Why does David do this?

The purpose of the Song of Deborah and Barak provides a clue. One scholar argues the song functions in Judges as a “challenge to the people to recognize and respond to divine activity with covenant fidelity.” Covenant infidelity led to Israel’s enslavement to enemies, so to avoid this fate, Deborah issues a challenge to recommit to the Lord.

Deborah is the only judge to lead the people in praise after the Lord delivered them, perhaps because she recognized that reliant praise was an important way to keep Israel’s eyes on the One who stabilizes fidelity. Her concern was justified, of course, because the next section of Judges narrates more infidelity.

Covenant infidelity led to Israel’s enslavement to enemies.

Similarly, David reigned after two eras marked by disobedience: the era of the judges and the reign of Saul. To liken one’s situation to that of Deborah and Barak is a humble move, because before and after their song, Israel rebelled. David recognized in his day the ever-present possibility of covenant infidelity, so he uses Judges 5 to do what Deborah did: humbly direct Israel’s gaze to the stabilizing grace of God for his weak people.

Seeking Undeserved Intervention (Psalm 83)

Psalm 83’s allusions to Judges are easier to identify: verses 9 and 11 contain names of places (like Midian; Judg. 4–5) and enemy leaders (like Sisera from Judg. 4–5 and Oreb from Judg. 6–8) from the Deborah (Judg. 4–5) and Gideon narratives (Judg. 6–8). The psalmist pleads with the Lord to repeat what he did in Judges 4–8 by defeating Israel and Judah’s ongoing enemies. But why does the psalmist choose stories from the book of Judges instead of stories from, say, Joshua?

In Joshua, God defeats Israel’s enemies in response to Israel’s obedient faith (e.g., Josh. 6–8). In Judges, though, God defeats the enemies in response to Israel’s repeated disobedience and disbelief. The psalmist is probably tacitly admitting that sin has led to ongoing enemy threats. Moses said, after all, that defeat by Israel’s enemies would often come because of covenant infidelity (Deut. 28:25). The writer of Psalm 83 seems to imply that God’s people need Judges-style intervention from God—deliverance when they deserve discipline.

Storying Parallel Failures (Psalm 106)

Psalm 106’s allusions to Judges read more like a story. The psalmist prefaces his narration of key events in Israel’s history with a thesis statement: “We have sinned with our fathers” (Ps. 106:6, LEB). Historical memory serves a repentant purpose. The writer begins by alluding to rebellion stories from Exodus and Numbers (Ps. 106:7–22) and then recalling how God saved Israel through the intercession of Phinehas and Moses (vv. 23–33).

The writer of Psalm 83 seems to imply that God’s people need Judges-style intervention from God—deliverance when they deserve discipline.

Then the psalmist turns to the events of Judges (vv. 34–46) but doesn’t mention an intercessor like Phinehas and Moses. The lack of intercessory leadership in Judges rings true when readers see what the Levites were doing in Judges 17–19 (i.e., idolatry and abuse).

Amazingly, even when Israel lacks a human intercessor, God still delivers them repeatedly (Ps. 106:43). Then the psalmist does some interceding of his own in verses 47–48, repentantly seeking another undeserved deliverance. The psalm humbles God’s people by likening them to Israel’s darkest hour of covenant infidelity because, even then, God’s grace prevailed.

Psalmists’ Use of Judges

“You’re just like your father.” Depending on the speaker and the father, this remark might be encouraging or humbling. If a biblical writer compared Israel to their forefathers Joseph or Joshua, it’d be encouraging. When psalmists compared Israel to stories in Judges, it was a way to humble the audience to help them (and us) rely on God.

These psalmists seem to have read the book of Judges and seen patterns analogous to their own sinful predicaments. Accessing unsavory biblical memories kept Israel from thinking too highly of themselves and helped them think more highly of God’s marvelous grace. Reflecting on these psalms and the way they view the past can do the same for us today.

News Source : https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/psalmists-sing-judges/

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.