“So, what’s your dissertation about?”

When I began my PhD work at the University of Edinburgh in 1999, I can remember dreading this question from my evangelical friends. I’d try to explain to them that I was working on a fourth-century manuscript of an apocryphal gospel (P.Oxy. 840) and comparing it with the text of the canonical Gospels. So my research pertained to ancient manuscripts, textual transmission, scribal features, and the variant forms of the Jesus tradition in early Christianity.

By this point in the conversation, most people’s eyes would glaze over.

In the 1980s and ’90s, topics like textual transmission and ancient manuscripts weren’t on the average believer’s radar. Most probably hadn’t even heard the term “textual criticism,” and if they had, they likely couldn’t define it (nor would they have much interest in it even if they could).

Sure, there were plenty of apologetics books during this time that the person in the pew might have read. But most were centered on broader issues like God’s existence, the creation-evolution debate, the New Testament’s historical reliability, or evidence for the resurrection.

In contrast, the field of textual criticism probably seemed narrow, mundane, and overly technical. To many evangelicals, it was a subject more suited for “liberal” scholars rather than those with historic Christian convictions.

There’s an element of truth to this observation. While textual criticism isn’t “liberal” or “conservative” in and of itself—as we’ll see below, scholars of any ancient text would need to establish, as much as possible, the original wording of that text—there weren’t many evangelical scholars in this field in the ’80s and ’90s. Consequently, the field seemed out of bounds for most Christians.

My, how things have changed.

Perhaps the change is most aptly seen in Wes Huff’s recent appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast. While the three-hour interview covered a wide range of subjects, manuscripts and textual transmission took center stage. Huff even showed Rogan a replica of the well-known manuscript P52, which is still considered the earliest fragment of the New Testament in our possession. That podcast went viral, and now everyone wants to talk about textual transmission and New Testament manuscripts.

Could it be that now textual criticism is finally, well, cool?

While it seems that textual criticism is as cool as it’s ever been (whatever that means), Huff’s conversation with Rogan isn’t the whole story. Most people don’t realize that textual criticism, and evangelicals’ role in that field, has been changing for 30 years. Put differently, Huff’s podcast appearance isn’t the beginning of changing perceptions about textual criticism but the result of them.

So, what’s been happening for the last 30 years that can explain why textual criticism is suddenly so popular? And what are the implications for how Christians can share their faith today?

Before answering those questions, we must define what we mean by textual criticism.

What Is Textual Criticism?

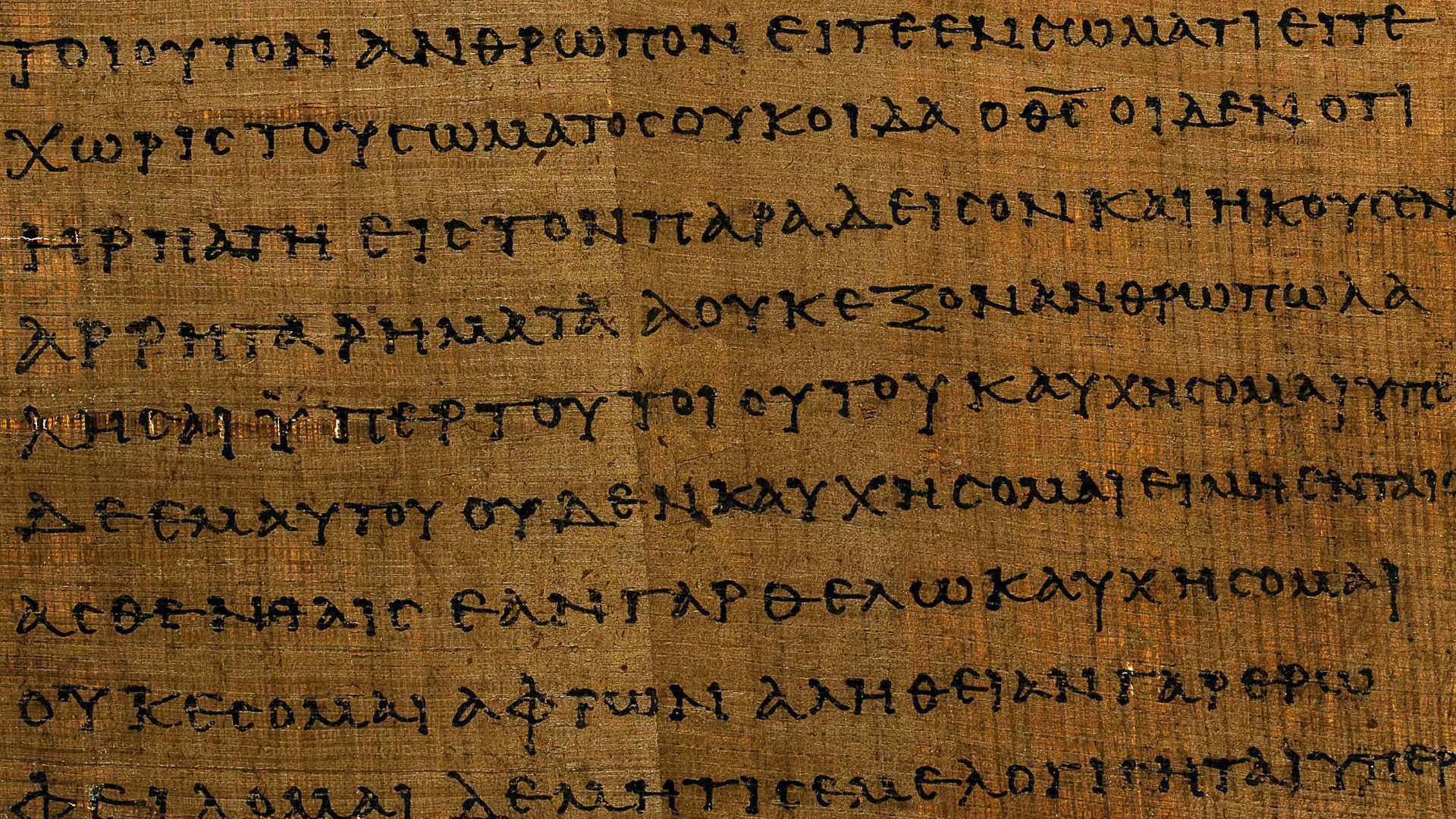

Outside of archaeology, the only way we can know what might have happened during a period of human history is because someone somewhere wrote about it. While people wrote on a wide range of materials—from stone to pottery to wood—the most common were papyrus or parchment, which are essentially ancient versions of paper.

If a person wrote a historical or literary document and wanted to see that document distributed, then copies would have to be made. Copies were done by hand, usually by trained scribes (although sometimes by amateurs). As documents wore out over time, more copies would have to be made so the text could be preserved for future generations.

During the copying process of any ancient document, scribes occasionally made mistakes. Most were just ordinary slips of the pen—spelling differences, word order changes, accidental omissions, and so on—but now and then, scribal changes would be more significant.

This means that when we compare copies of any historical document, there are likely to be points where the text is different. Unlike books published by a printing press, where all copies are (usually) exactly the same, hand-copied manuscripts have inevitable textual variations.

Here we come to the core purpose of the discipline of textual criticism, which is to restore, as much as possible, the original wording of any historical document. Other aspects of the discipline are also important (see discussion below). Moreover, there are debates about how accessible the “original text” actually is (and whether we can ever really reach it). Regardless, neither of these qualifications changes the main goal of the discipline, at least as it’s been historically practiced: to work toward reconstructing the original text.

The core purpose of the discipline of textual criticism is to restore, as much as possible, the original wording of any historical document.

The above discussion reveals that the discipline doesn’t pertain only to the study of the New Testament (or Old Testament). Every ancient text is in the same boat. This is a good reminder that the presence of textual variants isn’t something scandalous or shocking. On the contrary, it’s natural and ordinary. It’s an inevitable part of studying any historical text.

This isn’t to suggest, however, that all ancient documents are transmitted with equal degrees of fidelity. Some are preserved better than others. And a number of scholars (including me) have argued that the New Testament has been transmitted with an impressive degree of faithfulness.

Rise of Textual Criticism’s Popularity

With the above definition in mind, we now turn our attention to what has led to the broad-based interest in textual criticism over the last 30 years, particularly among evangelicals.

1. Responding to Challenges

Much of the interest in textual criticism among evangelicals can be traced back to the work of a former evangelical.

Bart Ehrman, longtime professor at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill and author of more than 30 books, did his PhD under Bruce Metzger at Princeton Theological Seminary. While he’d published on textual criticism in academic spaces for some time, in 2005 he published the New York Times best-selling book Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Ehrman did what no one had really done before, which is to write about textual criticism for a popular-level audience in a way that they actually wanted to read it.

But the effect of Misquoting Jesus was about more than accessibility. Ehrman used the book to directly challenge the Christian belief in the New Testament’s reliability. How can we trust the New Testament, Ehrman argues, if we don’t know the words of the New Testament?

While the New Testament’s textual integrity had been challenged before, this attack was different because of its widespread appeal. The discussion was no longer relegated to the distant halls of the academy. Now it was happening in the pews. Evangelical scholars felt obligated to respond. Thus, there was a burst of popular evangelical literature on the textual history of the New Testament.

2. Role of the Internet

It’s a truism that everything changed with the internet, and the discipline of textual criticism is no exception. Also in 2005—and perhaps not coincidentally—the Evangelical Textual Criticism blog was founded. This blog created an online space for high-level academic discussion (as well as networking and collaboration) about textual criticism from evangelical scholars.

Although the scholars associated with the blog have changed over the years, these are the current contributors: Peter Head, Tommy Wasserman, Peter Williams, Dirk Jongkind, Maurice Robinson, Peter Gurry, John Meade, Peter Malik, Peter Montoro, Christian Askeland, Amy Anderson, Elijah Hixson, Anthony Ferguson, Michael Holmes, Peter Rodgers, Bill Warren, Jean-Louis Simonet, and Martin Heide.

Of course, Evangelical Textual Criticism isn’t the only evangelical website devoted to discussing the transmissions of the New Testament text. There has been an explosion of such sites—too many to mention here.

3. Institutional Support

A number of groups and institutions have played a key role in sparking and sustaining evangelical interest in textual criticism. In 2005, I proposed, along with Stan Porter (as co-chairs), a new study group at the Evangelical Theological Society: “New Testament Canon, Textual Criticism, and Apocryphal Literature.” Stan and I had noticed there was no natural venue for the study of these important issues at ETS, which is the largest gathering of evangelical scholars in the world.

That study group has persisted for 20 years now, and we’ve had a great lineup of papers every year on various important issues related to textual criticism and beyond. It should also be noted that textual criticism (and canon) was the overall theme of the 2008 ETS Annual Meeting, with plenary papers by Chuck Hill and Dan Wallace on issues related to New Testament text and canon.

Another influential institution is Tyndale House, an evangelical study center at Cambridge University founded in the 1940s. Since Peter Williams became principal in 2007, Tyndale House has demonstrated a particular interest in issues related to textual criticism (not just among staff but also among visiting scholars and affiliated Cambridge PhD students). This interest is perhaps seen most aptly in the 2017 publication of the Tyndale House Greek New Testament.

Many other evangelical institutions have played a role in the rise of textual criticism (too many to mention here), such as The Center for New Testament Textual Studies at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary (founded in 1998 by Bill Warren),

4. Access to Digital Images

A real game changer in the field has been access to high-quality digital images. Such images have been available for a while at the Institute for New Testament Textual Research (INTF) website, operating out of Münster. Newer sites are now popping up offering exceptional access (for example, you can see Codex Sinaiticus and P75 with stunning clarity).

Particularly noteworthy is the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM), founded by Dan Wallace in 2002. The core of its mission is developing an online collection of digital images of New Testament manuscripts and acquiring new images of manuscripts that haven’t yet been properly cataloged and photographed. The CSNTM has made digital images widely available and has digitized more Greek New Testament manuscripts than any other institute.

For many years, the CSNTM has also offered rigorous internships, allowing students to be mentored in New Testament textual criticism. Many of these interns have gone on to pursue PhD work themselves.

5. Expanding the Discipline

In prior generations, textual criticism was largely focused on how to recover the original wording of manuscripts. And, as I noted above, this will always be the core goal. But in the last generation, the discipline’s goals have gone beyond the microevaluations of (possible) scribal changes.

One of those aspects is renewed attention to manuscripts as physical artifacts in their own right. Such a focus would involve issues like the origins of the codex, use of the nomina sacra, and paratextual features of early Christian manuscripts. A seminal work in this area is Larry W. Hurtado’s The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, which lays out the basic contours of how early Christians constructed and used their books.

Why does this matter for the rise of textual criticism among evangelicals? Because it highlights an aspect of textual criticism—the physicality of manuscripts—that’s not only more accessible but also, at least for some evangelicals, more interesting. People connect best to aspects of history they can see and (in principle) touch.

Role of Textual Criticism in Modern Apologetics

Evangelicals are in a position like never before to use textual criticism as part of the argument for the truth of Christianity and, more specifically, the trustworthiness of Scripture. Textual criticism no longer needs to be viewed as an arcane and narrow subdiscipline for critical scholars, with no connection to evangelical beliefs. On the contrary, it can play a significant role in undergirding evangelical beliefs.

Let me lay out a few reasons why textual criticism can be effective in our modern apologetic toolbox, along with a few important cautions.

1. Staying Focused

Apologetic conversations are notorious for getting off track. There are so many elements to discuss and so many objections that can be made that it’s hard to stay focused on the main point. One benefit of discussing issues related to manuscripts and textual transmission is that it keeps the focus on one of the core claims of the Christian faith, namely, that the Bible is a real historical document that can be trusted.

You could argue that the trustworthiness of the Bible is, in a sense, the whole enchilada. If someone accepts the Bible as true, many other things will fall into place from there. If someone rejects the Bible as true, it’s difficult to make progress on other important matters.

2. Keeping It Real

When we discuss the truth of Christianity with a non-Christian, much of our time is typically spent on discussing ideas or concepts. Does God exist? What’s he like? Who is Jesus? Why did Jesus have to die? Are there other ways to heaven? Are all religions the same? These are all important questions and will eventually need to be addressed. However, such discussions are difficult because they’re often so intangible. They’re philosophical, theological, and doctrinal; many people struggle to understand and follow them.

But over the years, I’ve noticed people respond differently to discussions of biblical manuscripts and textual transmission. They light up. This was evident in Huff’s discussion with Rogan (and in the many people who’ve heard it since). Why does this happen? Such topics make Christianity more concrete and tangible.

People connect best to aspects of history they can see and (in principle) touch.

The fact that manuscripts are real historical objects that can be seen and touched reminds people that Christianity has a real history behind it that can also, in a sense, be seen and touched. And this resonates with people searching for truth. They want to believe something real. Physical artifacts like manuscripts help them consider that Christianity might, in fact, be real.

3. Just the Facts

We have solid evidence that the New Testament has been transmitted with remarkable fidelity. Even a layperson can learn basic facts that highlight the integrity of this transmission process. Two key facts are worth mentioning:

- Number of manuscripts. As scholars seek to know how much any writing of antiquity has been changed, and, more importantly, as they seek to establish what that writing would have originally said (by tracing those changes through the manuscript tradition), the more manuscripts that can be compared the better. The higher the number of manuscripts, the more assurance we have that the original text was preserved somewhere in the manuscript tradition. Currently, we have more than 5,700 Greek manuscripts of New Testament writings (the number varies slightly depending on how they’re counted), some of which are complete and others of which are fragments. Notably, this is more manuscripts than any other ancient documents from this time period.

- Date of manuscripts. The textual critic doesn’t desire just a high quantity of manuscripts but also manuscripts that date as close as possible to the time of the original writing of that text. The less time between the original writing and our earliest copies, the less time for the text to be substantially corrupted. We have manuscripts of some books of the New Testament dating as far back as the second century, which is remarkably close to the original production of these documents in the first century. The earliest extant copies of most Greco-Roman texts from the same period are removed from the originals by more than 500 years.

While the above reasons make textual criticism a key part of our modern apologetics, two important cautions need to be mentioned.

We have more than 5,700 Greek manuscripts of New Testament writings, notably more than any other ancient documents from this time period.

First, be careful not to overstate what textual criticism can prove or not prove. It’s designed to ascertain whether a text has been reliably transmitted, not whether the statements within that text are actually true. Theoretically, a document could be transmitted carefully and still be false. So textual criticism doesn’t say everything that needs to be said about our New Testament writings. It will have to be supplemented with additional arguments for why the content of these documents is historically credible.

Second, remember that textual criticism is a technical field that’s sometimes misunderstood (and even misrepresented). It’s understandable if someone wants to make these technical matters as simple as possible, especially if he or she is talking to a lay audience. But sometimes this attempt to make something simple ends up making it simplistic and therefore inaccurate. If you want to talk about textual criticism, you’ll need to understand your limits and make sure your statements are grounded in the established literature in the field. For help in avoiding mistakes and pitfalls, see the collection of essays in the volume edited by Elijah Hixson and Peter Gurry, Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism.

Bright Future

It’s hard to believe we’ve reached a day when textual criticism, from the perspective of an evangelical like Huff, would go viral on something like Rogan’s podcast. I guess we could say textual criticism is finally cool. But, as I’ve argued above, it took a long time to get here. Over the last 30 years, evangelical scholars have engaged the world of textual criticism like never before, and it’s exciting to see the fruit now emerging from that engagement.

The future of evangelical textual criticism looks bright. With a slate of younger scholars ready to make their own contributions, I’m optimistic there will be more and more opportunities to demonstrate that Christian claims about the New Testament aren’t merely speculation or wishful thinking but rooted in real time and space, with a vivid historical record that can be seen and touched.

News Source : https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/textual-criticism-cool/

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.

Your post is being uploaded. Please don't close or refresh the page.